The balance between short-term and long-term goals was always going to make this a tricky season for Arsenal and Mikel Arteta. Over the past few years, Arsenal have fallen into the trap of not knowing which to prioritise. Should they develop younger, more talented players? Should they lean on more established pros? They’re tried to do both at once and have ended up failing on both counts.

The short-term hope is, rather bluntly, to be better. Better with the ball, better against the ball. The long-term goal is to be good enough to finish in the top four not just once but repeatedly. The long-term plan can’t be realised without short-term success and short-term improvement can’t be sustainable without a clear long-term plan.

And so Arsenal have spun around in circles since around 2017, like a dog chasing its tail, looking for short-term ways to realise their long-term goals and having no real long-term plan to make any short-term success sustainable. And that continued in Mikel Arteta’s first full season in charge.

Through a positive lens, you could consider that he had no pre-season and suggest matches were treated as a crash course for him to learn about his team, and about management, and for the players to learn about what he wanted from them. But the non-stop nature of the season meant there was no time to stop and consider anything. Lessons didn’t seem to be learnt quickly and Arteta clung to ideas that worked temporarily, hoping to ride on the positives rather than work out the kinks and find further improvement.

Maybe there wasn’t time for further improvement, but it meant we’re left with the feeling that a season has been lost. An unsustainably solid start turned into a disastrous first third of the campaign, a promising middle third slowed down when players picked up injuries, and the season fizzled ultimately out with us not really knowing if we’ve improved, if we’ve gotten worse, or even what Arteta wants his Arsenal to look like.

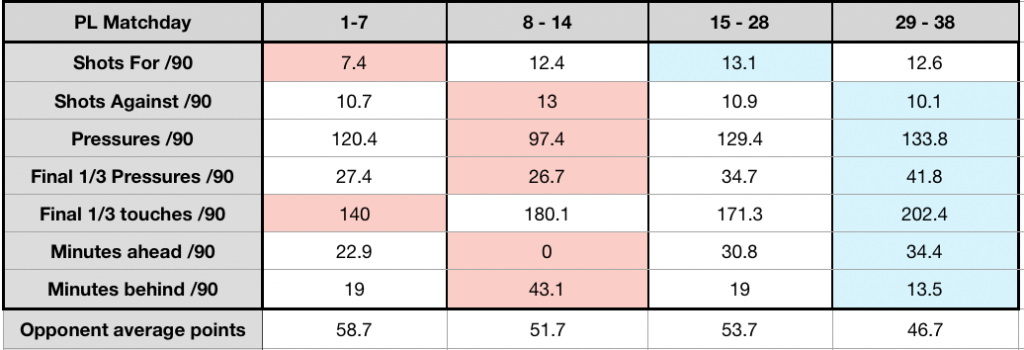

Breaking down or running through an entire season isn’t simple but Arsenal’s 2020/21 Premier League campaign can pretty reasonably be broken into four sections. Arsenal weren’t good, then were dreadful, then suddenly improved, then had to deal with injuries and ended the league campaign strongly (with an easy-ish run-in) despite an awful showing in the Europa League.

So, what happened, what changed, what have we learned and where does all that leave us?

So, what happened, what changed, what have we learned and where does all that leave us?

A conservative start

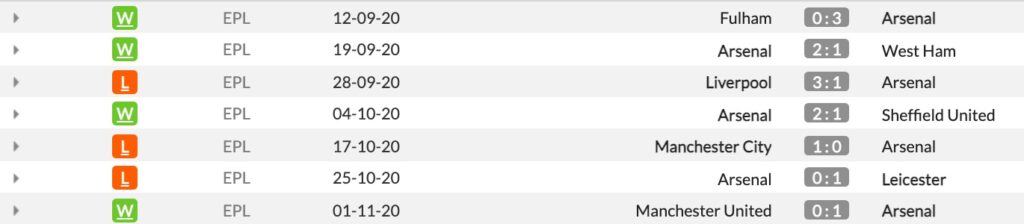

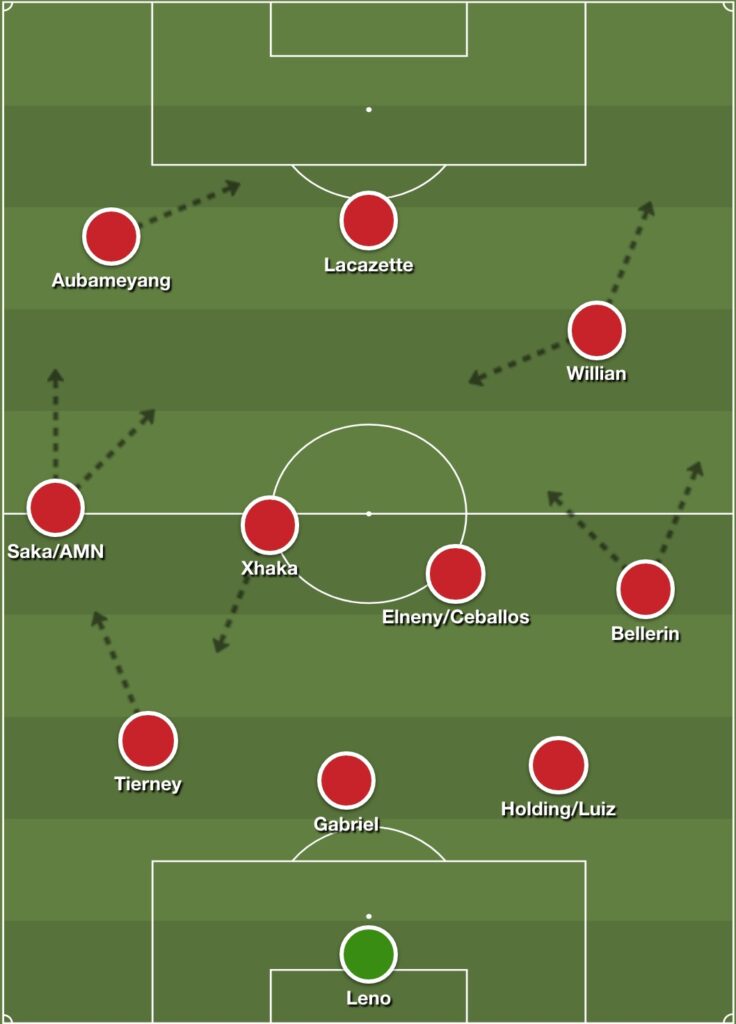

Arsenal came into the season and stuck with what had worked during the previous campaign’s successful FA Cup run. Three centre-backs, with Kieran Tierney pushing on from the left of the back three, two sitting midfielders, and Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang moving inside from the left.

Arsenal came into the season and stuck with what had worked during the previous campaign’s successful FA Cup run. Three centre-backs, with Kieran Tierney pushing on from the left of the back three, two sitting midfielders, and Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang moving inside from the left.

It was, generally, slow and ponderous in possession. By mid-November, there was an article on the Athletic detailing that Arsenal had the slowest build-up in the league. Only Newcastle had fewer than Arsenal’s 29 possessions per game ending in the final third.

It was, generally, slow and ponderous in possession. By mid-November, there was an article on the Athletic detailing that Arsenal had the slowest build-up in the league. Only Newcastle had fewer than Arsenal’s 29 possessions per game ending in the final third.

Arsenal’s attack is literally the slowest in the league, and tonight looks no different

£1/month offer at the moment, a deal that’s not around for much longerhttps://t.co/Crz4ug2LH2

— Tom Worville (@Worville) November 29, 2020

That meant very few shots and very few chances amid plenty of stale possession. Arsenal had to score when they did create something, because it would probably be their only decent effort of the game.

The team’s pressing was focused on stopping progression into midfield, not winning the ball back. This was fine in some cases, meaning the defence wasn’t exposed by a disorganised press, and it worked well at Old Trafford, with Manchester United struggling to find ways to move the ball from back to front as Alexandre Lacazette was focused not on marking the centre-backs but central midfielder Scott McTominay.

However, any team who played confidently from the back or directly upfield found life quite easy, seeing as Arsenal’s pressing was built to stop progression through the middle and little else. When teams managed to break through that initial mid-block, which didn’t work with too much intensity, Arsenal would drop back into a compact shape, more focused on protecting their own box with numbers rather than trying to win the ball in midfield or further forward.

However, any team who played confidently from the back or directly upfield found life quite easy, seeing as Arsenal’s pressing was built to stop progression through the middle and little else. When teams managed to break through that initial mid-block, which didn’t work with too much intensity, Arsenal would drop back into a compact shape, more focused on protecting their own box with numbers rather than trying to win the ball in midfield or further forward.

Let's begin by addressing Arsenal's press intensity, throughout the last 47 Premier League games, and its progressive decrease.

The intensity gunners have been applying since the start of the season is quite worrying. pic.twitter.com/yScalsY6ti

— Victor (@victorrenaud5) November 26, 2020

Even though the season season started with plenty of slow, uninspiring football, Arsenal still picked up points. But only because a lot of narrow margins were going our way. The opening day win against an abject Fulham aside, our victories came because we took our only real chance (v West Ham, Man Utd) or were clinical during an unusual flurry of activity (Sheff Utd) but never because we dominated the opposition.

Arsenal took six or fewer shots in four of the opening seven games, winning three of them and losing one. The team also conceded fewer than 10 shots in four of the opening seven games. Matches involving the Gunners were the opposite of end-to-end. And then they got worse.

7 games, 0 wins

At least in that early spell, when games were close and Arsenal weren’t doing much, they were mostly just about doing enough, getting ahead in games even without creating many chances. Then we saw what happens when you play badly and things aren’t going your way. When you pick up a red card every other game and the opposition start scoring with their only decent chances while you miss yours.

At least in that early spell, when games were close and Arsenal weren’t doing much, they were mostly just about doing enough, getting ahead in games even without creating many chances. Then we saw what happens when you play badly and things aren’t going your way. When you pick up a red card every other game and the opposition start scoring with their only decent chances while you miss yours.

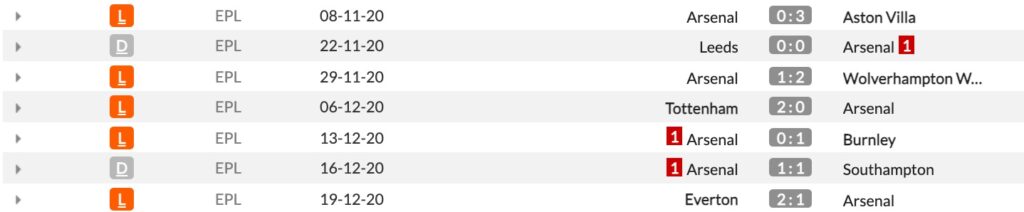

For over one month, Arsenal were the second worst team in the Premier League. Only Sheffield United collected less points. In seven league games, Arsenal lost five, scored three goals, picked up three red cards, earned just two points, and didn’t win a single game.

Arsenal did not even take the lead in ANY of these seven matches.

There was some misfortune — the own goal that allowed Burnley to win, the fact Spurs scored with their first two shots on target, the timing of the red card against Southampton when Arsenal were on top — but none of that can excuse the performances.

Arsenal entirely struggled to create good chances. Things looked far too rigid, there was no central presence to stretch teams or move defenders. It was a problem when games were level and one that worsened when the team constantly found itself behind, with opposition sides flooding the middle and Arsenal lacking the movement and fluidity to move defenders. There were no questions asked of opponents. They could stand in position, completely secure.

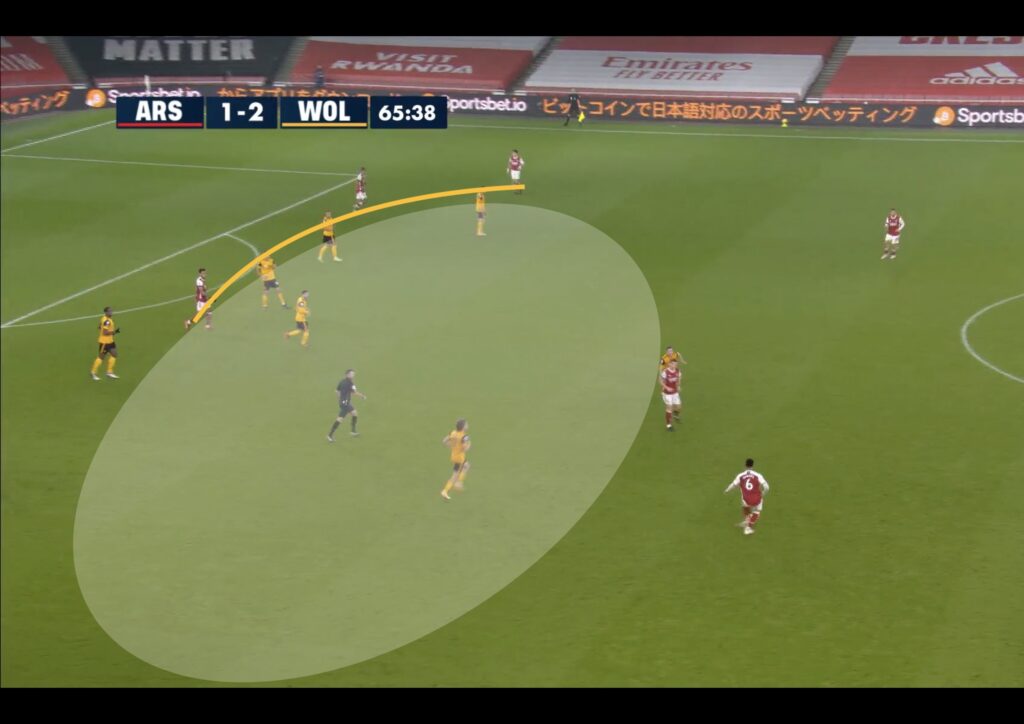

It became increasingly common to see Arsenal frustrated against sides, with the Gunners incredibly easy to defend against. There was width across the frontline but the players were completely static, with nobody stretching the defence with runs in behind, no players dropping off the frontline to drag a defender out, nobody standing in spaces to make a defender question whether or not that was still his man. Scenes like this became the norm.

It became increasingly common to see Arsenal frustrated against sides, with the Gunners incredibly easy to defend against. There was width across the frontline but the players were completely static, with nobody stretching the defence with runs in behind, no players dropping off the frontline to drag a defender out, nobody standing in spaces to make a defender question whether or not that was still his man. Scenes like this became the norm.

if I speak, I'm in a big trouble

(Saka 'merged' with Nketiah if you were wondering, another reason to transform it to the interactive tool one day) pic.twitter.com/2ds8iIoGBk

— Piotr Wawrzynów (@pwawrzynow) October 22, 2020

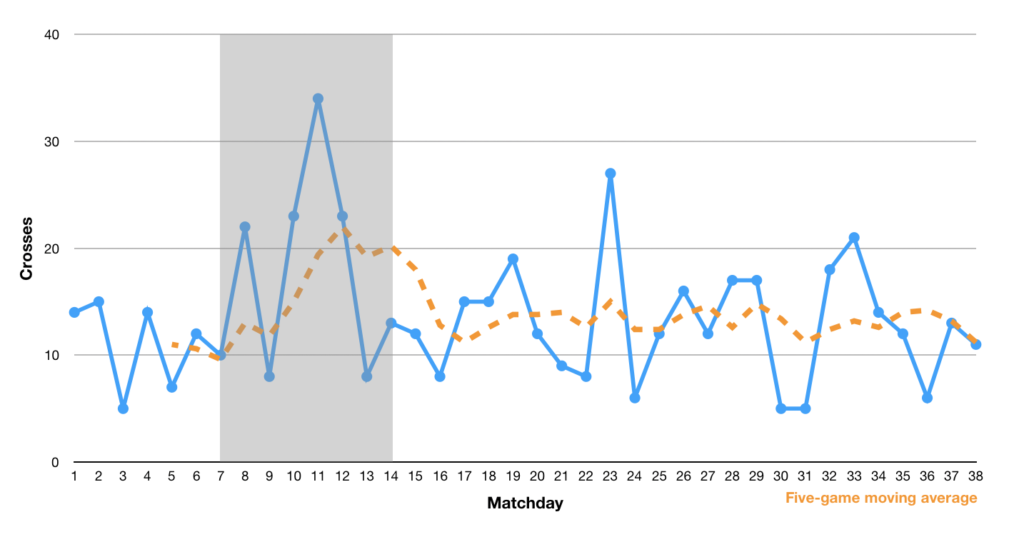

With Arsenal’s central midfielders drifting wide, there was an attempt to outnumber opponents on the flanks. But even when that worked, it meant Arsenal had worked themselves into nothing better than a poor crossing position, only to launch the ball into a sea of defenders.

Even when Aubameyang in the middle made the right run, which he often did, he wasn’t found. His goalscoring drought was a result of Arsenal’s issues in attack, not the cause. His movement was not much different to how it was at his best, the ball just didn’t arrive.

— Arsenal Tactics (@ArsenalVids1) December 15, 2020

It’s no surprise to see that Arsenal’s crossing numbers went up during this spell. A team out of ideas or any creativity in the centre of the pitch ends up crossing the ball more, and that’s exactly what was happening. Without any central presence, Arsenal found play easily funneled out wide, and then just swung the ball in to forwards not suited for that style of play. It was meat and drink for the defenders.

Arsenal put in 20 or more crosses in just six Premier League games all season and four of those matches were during the seven-game win-less run.

To compound the poor attack, Arsenal repeatedly had stupid mistakes punished as the need for points increased and players became more desperate. Nicolas Pepe lost his cool at Leeds, Granit Xhaka did the same against Burnley before an Aubameyang own goal saw the Clarets leave north London with all three points just when things were looking a little better. Three days later, Arsenal were on top in a game again when a rush of blood to the head saw Gabriel pick up two yellow cards, one after the other, in the draw against Southampton.

To compound the poor attack, Arsenal repeatedly had stupid mistakes punished as the need for points increased and players became more desperate. Nicolas Pepe lost his cool at Leeds, Granit Xhaka did the same against Burnley before an Aubameyang own goal saw the Clarets leave north London with all three points just when things were looking a little better. Three days later, Arsenal were on top in a game again when a rush of blood to the head saw Gabriel pick up two yellow cards, one after the other, in the draw against Southampton.

Whether or not the team every actually found rock bottom is hard to know but it felt like it at the time and Arteta could’ve had no complaints if he had lost his job. Sitting 15th at Christmas, four points above the relegation zone, it felt like he was clinging on as fans faced up to the prospect of a relegation battle, something that was, despite an obvious, unthinkable for a club which has not finished lower than 12th since 1976.

‘Play the kids!’

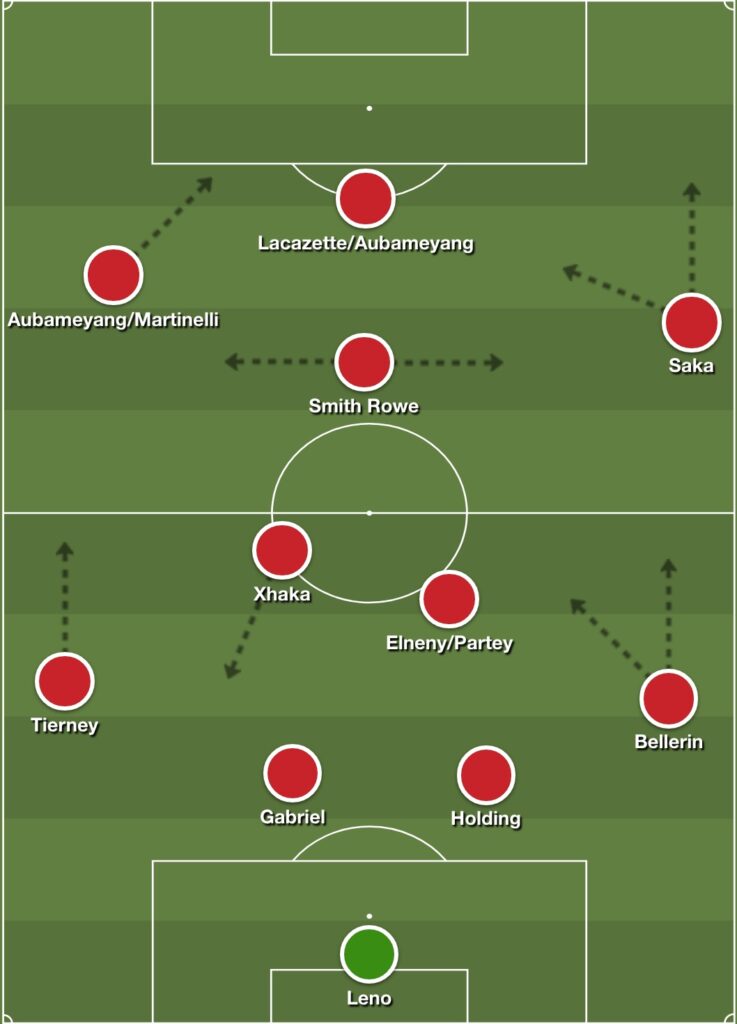

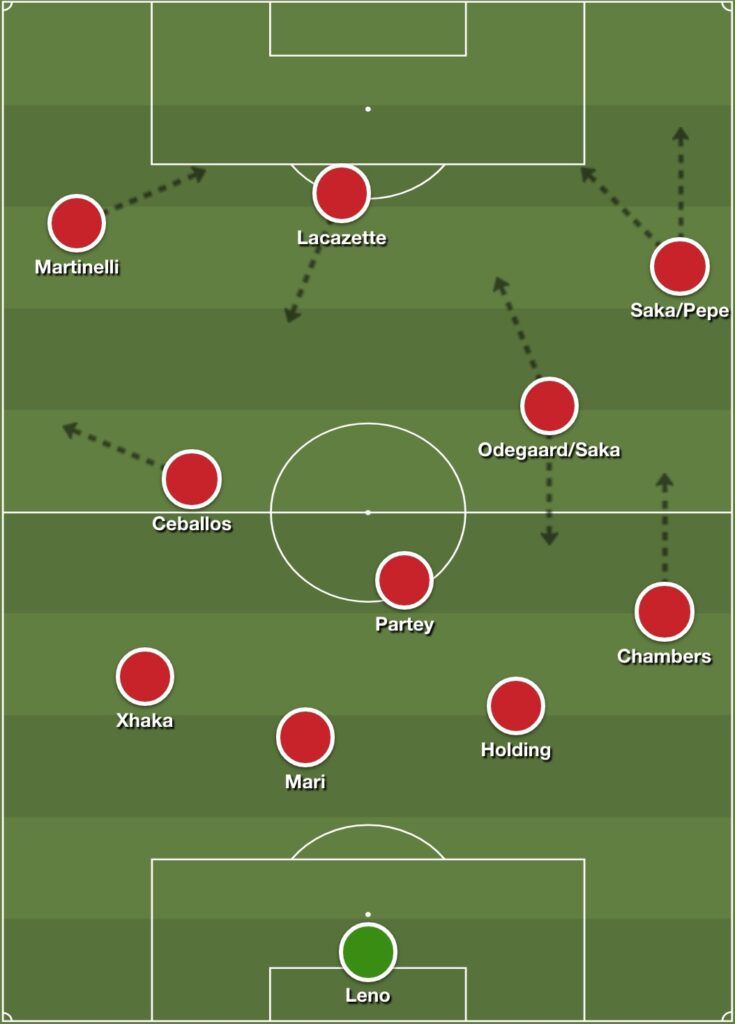

And then things changed. The back four became permanent, with the back three only seen once (Chelsea away) after Christmas. Arteta had flirted with a 4-2-3-1 during the win-less run, using Joe Willock and then Alex Lacazette as the number 10, before reverting to a three-man defence for games against Southampton and Everton. But Chelsea on Boxing Day was something brand new entirely as Emile Smith Rowe came into the starting XI and Bukayo Saka played on the right, where he could drift inside and impact the game.

Smith Rowe made Arsenal fluid. He filled the gaps. He made a slow team quicker. The offensive midfielder instantly looked to get into those central areas that Arsenal had been vacating, between opposition players, dragging them towards him to create space elsewhere. Arsenal suddenly had players between the lines.

Smith Rowe made Arsenal fluid. He filled the gaps. He made a slow team quicker. The offensive midfielder instantly looked to get into those central areas that Arsenal had been vacating, between opposition players, dragging them towards him to create space elsewhere. Arsenal suddenly had players between the lines.

I can't believe Arsenal play a proper system today. Mikel, blink twice if you need help. pic.twitter.com/LhN8NT7fKN

— Piotr Wawrzynów (@pwawrzynow) December 26, 2020

When Smith Rowe received the ball, play accelerated. He looked to play passes around corners, or receive on the half-turn and drive at back-lines. He wanted to receive the ball in tight areas and he would get it, give it, and then go for the return. And it was infectious, Saka joined in.

When Smith Rowe received the ball, play accelerated. He looked to play passes around corners, or receive on the half-turn and drive at back-lines. He wanted to receive the ball in tight areas and he would get it, give it, and then go for the return. And it was infectious, Saka joined in.

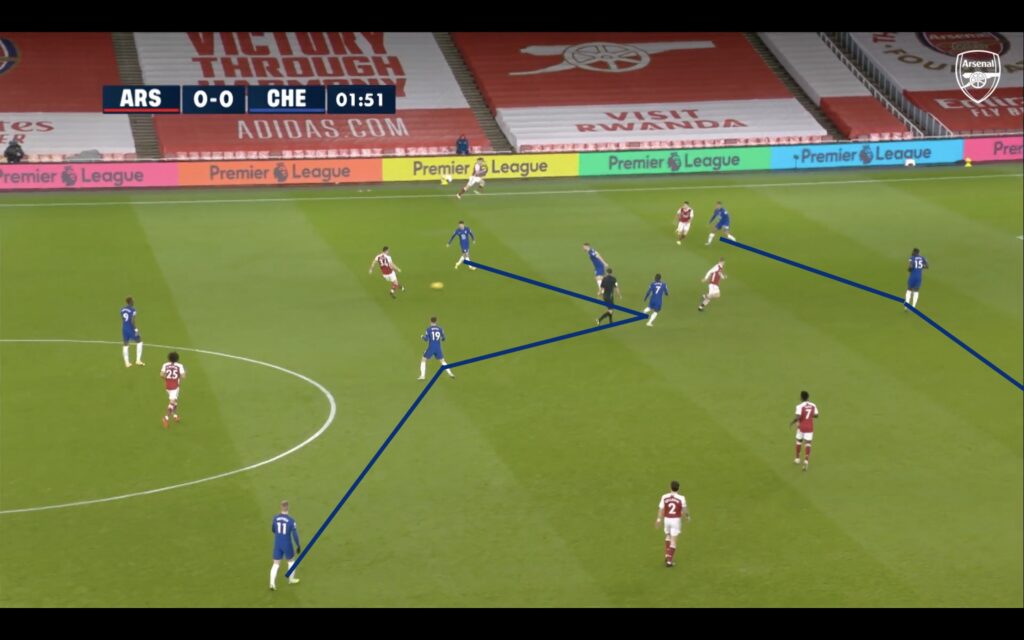

Smith Rowe transformed the speed of the team against Chelsea and then a few days later against West Brom in one of the performances (team and individual) of the season. The image below doesn’t look like a dangerous situation at all. It takes the players to force impetus into a situation like that to turn it into something. Saka dropping off the frontline is already an improvement on the movement of the forwards a few weeks before, but he isn’t easy to find and his positioning alone isn’t enough without movement around him.

That’s what Smith Rowe added to the side. He punched the ball into Saka without hesitation, then followed it, bursting outside into the space his fellow youngster had vacated.

That’s what Smith Rowe added to the side. He punched the ball into Saka without hesitation, then followed it, bursting outside into the space his fellow youngster had vacated.

Two quick passes later, he was in.

Two quick passes later, he was in.  Smith Rowe’s inclusion and energy helped Arsenal press further upfield, too. With an extra midfielder instead of an extra defender, Arteta’s side could push upfield and force teams backwards. Instead of the striker blocking a pass into midfield, that was not Smith Rowe’s job, and the striker — Lacazette against Chelsea — could press the centre-backs or then the goalkeeper and force the ball further back.

Smith Rowe’s inclusion and energy helped Arsenal press further upfield, too. With an extra midfielder instead of an extra defender, Arteta’s side could push upfield and force teams backwards. Instead of the striker blocking a pass into midfield, that was not Smith Rowe’s job, and the striker — Lacazette against Chelsea — could press the centre-backs or then the goalkeeper and force the ball further back.

The results improved but it wasn’t just that, but they were actually deserved. Something had clicked and Arsenal played, for a while, the best football of Arteta’s time in charge.

The results improved but it wasn’t just that, but they were actually deserved. Something had clicked and Arsenal played, for a while, the best football of Arteta’s time in charge.

After last night, this is the first time in Arteta's reign in which Arsenal have created better chances than they've conceded over any ten game stretch.

Turning point? pic.twitter.com/KW38g318Xz

— Tom Worville (@Worville) January 19, 2021

It wasn’t entirely convincing and there still wasn’t enough in some games when the team went behind early (Aston Villa, Man City) as the struggle to create plenty of chances continued. Still, there were finally some wins from behind (Southampton, Leicester, Tottenham) and some much improved performances. The north London derby stood out as Arsenal flew out of the blocks for one of the few times this season, even if they weren’t rewarded with an early goal. The attack wasn’t superb but it was no longer terrible.

And taking the lead makes a huge difference. Having not done so in any of the previous seven PL games, Arsenal were ahead at some point in 11 of these 14 fixtures. Of the other three, two saw Arteta’s side concede within two minutes (Man City, Villa) and the other was a goalless draw against Man Utd.

Arteta has consistently favoured keeping games tight, sacrificing some creativity in order to limiting the chances at the defensive end. And this run showed how well that works as long as you don’t ever find yourself behind in a game, as well as an improvement when it comes to coming from behind.

Little to play for

The previous few months had seen Arsenal go from consistently awful to consistently the better side, even it wasn’t always by a huge margin. For the last three months, the team was consistently disappointing and then consistently good again when it was too late. Basically, the 3-3 draw at West Ham both kicked off and summed up the run-in.

The previous few months had seen Arsenal go from consistently awful to consistently the better side, even it wasn’t always by a huge margin. For the last three months, the team was consistently disappointing and then consistently good again when it was too late. Basically, the 3-3 draw at West Ham both kicked off and summed up the run-in.

A reliance on individuals and a formula that worked was ruined when injuries struck in late March and early April. Kieran Tierney, who missed a bit of the positive winter spell, absent for defeats to Wolves and Villa, was sidelined again for the majority of April. Smith Rowe also missed a few games, Odegaard started well but faded after an injury of his own, and Xhaka was pushed to left-back and then injured as well, Aubameyang had malaria. What had worked was no longer an option and Arteta can reasonably be accused of over-complicating things as he looked for an alternative approach.

The reliance on individuals and a formula that worked was reminiscent of the end of Unai Emery’s first season; Arsenal won when Ramsey, Lacazette, Aubameyang played (and played well) and couldn’t win when they didn’t.

The reliance on individuals and a formula that worked was reminiscent of the end of Unai Emery’s first season; Arsenal won when Ramsey, Lacazette, Aubameyang played (and played well) and couldn’t win when they didn’t.

Gabriel Martinelli was the bright spark but his importance illustrated the team’s weaknesses. He was so exciting and dangerous because nobody else was. He broke free of the strict structure, he added acceleration and verve and flair to a team that naturally lacked those things, not unlike Smith Rowe in the winter months. But, over the last couple of months, Arsenal weren’t as bad as in the autumn but not as good as in the winter. And where that leaves us is anybody’s guess.

What’s next?

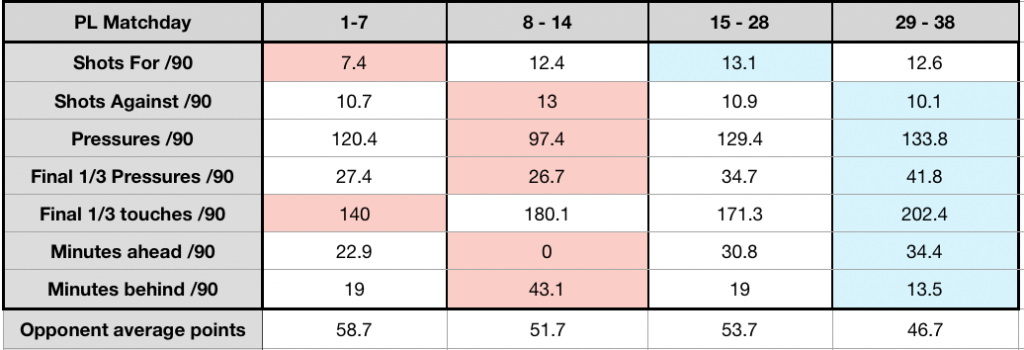

It’s clear Arsenal have played with more intensity since Christmas and results have improved drastically, though that isn’t hard when they were so terrible in the autumn. Still, Arsenal have picked up a lot of points over the final 24 games of the season and deservedly so. That feels like a long enough period for us to not write off as a fluke but actually take as encouragement while still accepting the team is not where anybody wants it to be.

After a horrible start to the season, Arsenal have undeniably been much improved since Christmas. And the numbers bear it out: more shots for, fewer conceded, higher and more intense pressing, more time in the opposition third. More minutes ahead and less time spent trailing.

There is room for improvement still, absolutely. In all of these areas. But there is also optimism to be found. By December many fans had lost faith that things could be turned around by Arteta and his players but they have done at least that. There hasn’t been much excitement amongst the fanbase during the run-in and understandably so. There has been little to play for with games against weaker opposition and alongside European disappointment as well as the backdrop of Europa League failure and the Super League debacle.

There is room for improvement still, absolutely. In all of these areas. But there is also optimism to be found. By December many fans had lost faith that things could be turned around by Arteta and his players but they have done at least that. There hasn’t been much excitement amongst the fanbase during the run-in and understandably so. There has been little to play for with games against weaker opposition and alongside European disappointment as well as the backdrop of Europa League failure and the Super League debacle.

Disinterest peaked. But the league results have continued to be impressive and even the most critical fan would fail to argue that performances were as poor as in the opening four months of the season. Arsenal have improved. The introduction of younger attackers has seen the team work with more intensity against the ball and the defence has enjoyed some stability while the attack has done enough to churn out at least one goal in most games. There are still big question marks about Arteta’s side when they go behind but they have at least improved in those situations as well as making sure they now spend considerably more team leading rather than trailing.

The problem when it comes to evaluating this season is it remains unclear what Mikel Arteta wants a Mikel Arteta team to look like. How much of the first half of the season was an Arteta side? How much was the second half? How much did he, rightly or wrongly, compromise what he wants his team to look like because of a lack of faith in the players? Why has he been so slow to adapt and learn seemingly obvious lessons? And will he use the time to reflect now that he finally has some?

Every club has had a hard season – the pandemic, the schedule, the lack of fans, the lack of a pre-season – but we were, to be fair, the only one to tackle all of it with a novice manager. Now, though, there will be no more excuses. There is a pre-season. There is more time to train.

And there is nowhere left to hide.