It was strangely appropriate that the winner, scored by Nacho Monreal, was a scuffed shot, although it was still hit accurately enough to evade the reach of Michel Vorm and creep into the bottom corner. Because the game was played with such precision – meticulousness that was painstaking at times that meant play was often broken down in the final third by delayed decision-making – as both teams seemingly tried to score the “perfect” goal. Swansea City nearly did that in the first-half as a move which started at the back, went forward, went back again and finally advanced down the right-flank and ended with the full-back, Angel Rangel, screwing a shot wide. His scuffed effort, however, wasn’t able to find the back of the net.

A moment of brilliance might have been even more fitting for a winner. Indeed, the best chances in the game before Arsenal eventually prevailed 2-0, fell to the most skilful players on the pitch; Santi Cazorla, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain, who hit the crossbar twice, and Pablo Hernandez. But the match was played with such perfect control and technique, that it felt like it had to be something really special to set the two sides apart.

Indeed, good technique, while widely accepted as an essential weapon, is rarely seen as a game-changing factor in the grand scheme of a result. Having good technique usually means simply being able to control the ball easily, weigh passes appropriately or maintain one’s balance when shooting. Occasionally, however, technique is the difference between winning and losing. In this case, both Arsenal and Swansea passed the ball at such a high level that on the face of it, which is a rarity in the modern game it must be said, it was difficult to determine who had the edge technically. As such, it confirmed that there is a level beyond mere technique which sets the best players apart.

To understand where I’m going, let’s look at the passing stats. Swansea had 56% of the possession and made more passes, 651 to Arsenal’s 492. That’s no mean feat considering Arsenal are the best passers in the league: so why weren’t Swansea able to convert that superiority into goals? The simple answer is that they don’t possess the same level of players as Arsenal do and in that sense, it’s correct. Santi Cazorla was miles ahead of anyone on the pitch – even his own team-mates – while Mikel Arteta’s presence loomed far larger than his opposite number, Leon Britton. But that’s just touching on the real answer and that is the best players are set apart by what’s in their head. That may not seem like a startling revelation but it’s something that is hard to describe.

It’s accepted that athletes process lots of decisions in a short space of time, but the best ones makes the correct ones more often. That was the theme for much of the game between Swansea and Arsenal before Monreal broke the deadlock. Moves would break down in the final third because players would make the wrong pass, or choose the option to shoot or cross. It was no surprise then that it was who Arsenal made more forays into the final third than Swansea (169/119) because they knew what to do with the ball better than their opponents.

On the one hand, their game features more purpose than Swansea’s, who are content to pass it around the back while Arsenal are eager to push forward at every opportunity. But on the other hand, there is an inexplicable edge that Arsenal’s forward players hold. It’s as Thierry Henry says: “I’d say 40 per cent of my game is [based on instinct]. But I always know where my teammates are before I receive the ball. If you can win time on the pitch – have a look before you receive the ball, see things before everyone else – that’s the difference between an average player and a player who illuminates the game.”

Good decision-making can also be applied to the defence. Because it was another game in which the performance at the back was assured and another game in which the team kept a clean sheet. Arsene Wenger stated that his side defended “high up the pitch” which is not to say they pressed particularly aggressively, but they tried to squeeze the space in which Swansea could play. So the back four still pushed up, but because the space was compressed in front, unlike the 2-1 defeat to Tottenham Hotspur, it eliminated the errors that would normally be associated with the high-line.

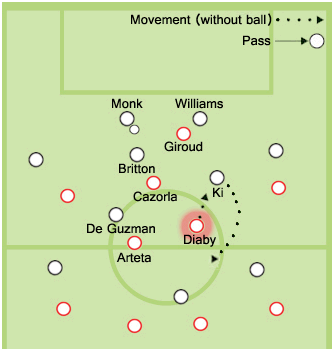

Arsenal’s defensive performance wasn’t always perfect, however, particularly in the first twenty minutes where Swansea dominated. When two 4-3-3’s face each other, it’s obvious who to pick up. But Abou Diaby continuously found it difficult as the midfielder in between – or the spare midfielder you might say (as in not the holder nor the main playmaker) – to decide whether to stay tight or hold his position. The midfielder he was supposed to be marking was Ki Sung-Yeung, who was also Swansea’s spare midfielder, and the South Korean was constantly able to find space to evade Diaby’s attentions.

As the half wore on, however, Diaby got better and showed glimpses of what type of player he could be for Arsenal, driving forward, winning the ball back (which he did 6 times, the most of all the Arsenal players) and released the ball quicker. But Diaby stuck out because his decision-making wasn’t quite as good as his team-mates around him. Once he gets that right, it could make all the difference.