Even this early on in the Premier League season, there is a trend: teams are abandoning the left-flank. In his first two matches in charge, the 2-0 Community Shield win over Wigan Athletic and the 4-1 league win over Swansea, David Moyes has used Danny Welbeck in a roving role, flitting in and out between striker and a wide player. In the last few seasons, Manchester City have done the same, giving David Silva freedom to cut inside. Liverpool do it with Philippe Coutinho, Tottenham Hotspur with Nacer Chadli or Gylfi Sigurdsson and Everton with Steven Pienaar.

There are plenty of good reasons for this: firstly, top teams are usually stockpiled with attacking talents therefore the flanks offer one way of fitting those players in. Of course, as the majority of these players are right-footed and are creative schemers, placing them on the left side affords them the freedom of still being able to get involved in the area of the pitch they most crave: the middle. Then there’s the increased importance of the full-back in the modern game as an attacking potential, therefore as such, narrowing one flank opens up space for them to get forward.

Brendan Rodgers, Liverpool’s coach, rather clunkily christened this position as the “false winger”. But the term is helpful because it helps distinguish those players who players who cut inside simply because they’re placed on the flank opposite to their preferred foot (making them an inverted winger such as Eden Hazard or Arjen Robben). The trend that we are seeing with the top Premier League teams is different, however, because these wide players are roaming inside very early in the build-up and sometimes even abandoning the flank it completely.

Of course, we’ll see how long this lasts as surely one or two of these coaches will revert to a pragmatic approach in order to get results. However, coaches realise that they need to encourage combination play in the centre as often as possible and as such, the roving wide player gives them an extra man whilst still retaining balance in the side. “David [Moyes] was talking about how everything was going through the middle area of the park,” says Scottish FA’s director of football development Jim Fleeting. “If we were working at attacking wide areas, you have to recognise that everything has to go through the middle at some point.”

It’s a tactic Arsene Wenger has regularly used in his 16 years in charge of Arsenal. He abandoned it for a while as Arsenal experimented with a Barcelona-style 4-3-3 and by playing “strikers” on the flanks, but in the form Santi Cazorla, it’s made a comeback. (Actually, Yossi Benayoun showed Wenger the way forward in the last months of the 2011/12 season).

Against Fenerbahce on Wednesday, Cazorla constantly drifted inside to create an overload, and then, as the play got sucked into the centre, he pinged the ball out wide for Theo Walcott to cause menace to the backline. We saw that combination for Arsenal’s third goal as Cazorla’s accurate cross-field pass found Walcott who controlled expertly before being brought down for a penalty. (And for the first goal, we saw the other advantage it gives Arsenal when he drifts inside: the extra space it opens for the full-back as it was Kieran Gibbs who opened the scoring).

The Cazorla-Walcott combination reveals another crucial dynamic to the way Arsenal play this season: how the two sides, the left side and the right side, differ going forward. The left side is more intricate, featuring neat little combinations while the right side is more direct; you will often see one-twos played before attempt to spring someone in behind. Much of it is down to Walcott who’s vital to the team because of the way he transforms Arsenal’s tippy-tappy style.

Indeed, at Fenerbahce, Arsenal’s two most creative players, Cazorla and Tomas Rosicky passed to Walcott 10 and 9 times respectively, indicating some sort of reliance on feeding the Englishman.

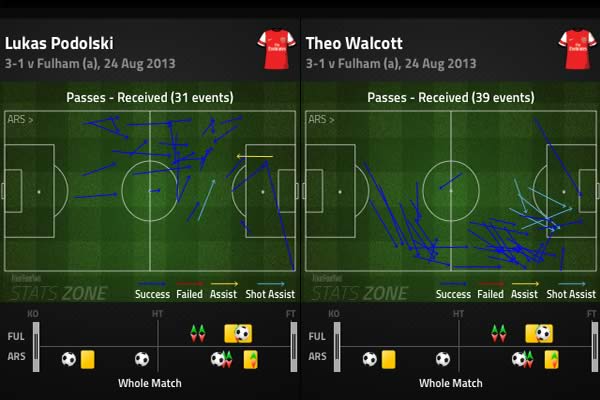

When Lukas Podolski and Walcott both start together, as they did against Fulham, the strategy for both the left and right flank is broadly the same – some may say too similar. But Podolski works because he can contribute to both sides of Arsenal’s game. His short passing and movement is superb, while still providing a goal threat. His two goals against Fulham highlight those qualities, both times arriving late in the box and finishing clinically. Cazorla might get the nod as he gives Arsenal more security in possession but Arsenal’s is a “game is based on very quick combinations” and both contribute in their unique way. You can say it’s the same for the way Arsenal use the two flanks too.

Ramsey runs the show

Normally such a stiff competitor for Arsene Wenger, all Martin Jol could do after his Fulham side were beaten 3-0 was to praise the opposition. He said: “If you see Santi Cazorla, he is one of the best players who can play with two feet – he can score with his left and right. (Theo) Walcott with his pace, (Olivier) Giroud is getting better and better, and their midfield – you can’t figure out who is the defensive midfielder and who is the offensive midfielder because they rotate all the time.”

The final point is the reason why Fulham were unable to cope with Arsenal; they just didn’t know who to press. If one of the midfielders got tight to Aaron Ramsey, another midfielder, Cazorla or Rosicky, would drop back and help Arsenal circulate the ball. As a result, Fulham didn’t press but stood off, and Arsenal were able to dominate. From a defensive viewpoint, the lack of a defensive midfielder didn’t hinder Arsenal much, mainly because of the growing stature of Ramsey. His positioning was excellent while Rosicky, his central midfield partner was not. Never mind, Ramsey’s extraordinary fitness levels almost allowed him to cover for two positions.

Mertesacker can pass

It’s easy to create a perception of the type of player Per Mertesacker is just by looking at him. He’s tall, therefore he must be good in the air (his jump is one of his weak points), and as he’s tall, he must be slow (but he compensates because his positioning is clever). Taking his passing statistics for the Fulham match (61/63 passes at 97%) and generally for last season (which was the best in terms of accuracy), it’s easy to guess that they were simple passes – but they weren’t.

Mertesacker’s mantra is to keep the ball moving and usually on the floor therefore he might pass to somebody under pressure but he does it to get rid of the marker. The receiever will send it back to him and Arsenal will start again. For Arsenal’s second goal at Craven Cottage, Mertesacker showed firstly, he’s not scared of adapting to Arsenal’s passing game by stretching wide across the pitch.

Then, he played an incisive pass through two Fulham midfielders straight to Podolski’s feet and that gave the impetus to start the attack. For the third goal, people remember Olivier Giroud’s touch and then Podolski’s finish but one must remember where the goal originated from: Mertesacker’s interception – in the box – before lofting the ball with his left foot perfectly onto the laces of Giroud. At least, I’m sure that’s exactly how he imagined it as he attempted the pass.