If you are my age (mid-30s) or a little older and you’re an Arsenal fan (if you’re reading this, there’s an excellent chance that you are), Ian Wright is probably your hero. The constituent parts that make up a ‘club legend’ are complex and difficult to define, but some players merit the tag by consensus and there can be no doubt that Wright emphatically meets that mark.

I started going to Arsenal regularly in 1992 and it’s difficult to overstate how much Wright came to define my early Arsenal memories. Supporting a club is, broadly, about attachment really, about belonging to something bigger than yourself but that becomes immediately bound up in your personal identity.

Every now and then a player comes along who, whether intentionally or otherwise, becomes the symbol for your team. I think Patrick Vieira did that during his Gunners career, I certainly know that members of my family would identify other cult heroes like Liam Brady and Charlie George in a similar fashion.

It’s not just that they were great players, it was the unruliness with which they played that made them so attractive to Arsenal fans. Brady’s untucked shirt and insouciance, George’s unkempt mane and fiery temper. Players like this become totem poles for supporters, the players we live through vicariously. Ian Wright was that symbol for the 1990s Arsenal fan.

At school, Wright was the player everyone spoke about when the topic of Arsenal found its way into conversation. My mates that supported Arsenal absolutely loved him and everyone else hated him. He pretty much always produced something worthy of playground conversation on a Monday, whether it be an instinctive finish, a goal celebration or a “disciplinary incident.”

When Arsenal released their first set of Nike shirts in 1994, they introduced a collar for the first time in some years. Wright wore his collar tucked in to create a round neck effect. Needless to say; me and every other Arsenal fan at football training with the Nike shirt followed suit. I certainly feel less embarrassed about mimicking his shirt tailoring than I do admitting to copying some of his reggae celebration routines with Kevin Campbell.

I grew up not far from where Ian did, in South London and I still live in the Lewisham area now. Arsenal possessing a core of South London reared talent during my formative years was very important to me and other Arsenal fans at my school. Wright, Rocastle, Kevin Campbell and Michael Thomas all grew up locally to us and I am convinced that the club was so popular with people my age south of the river for this reason.

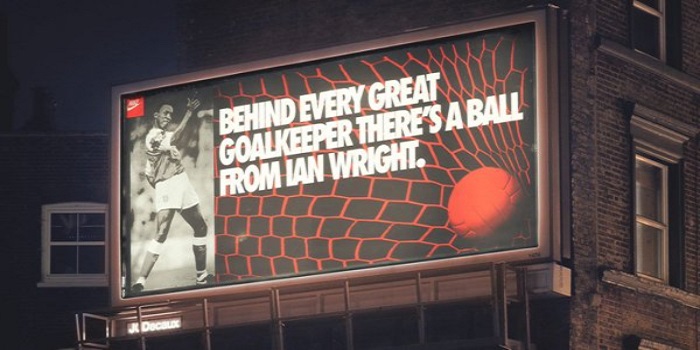

Wright was a cultural touchstone for the club, as well as the team’s reference point. I remember vividly the back-and-forth billboard campaign between Nike (Wright’s boot sponsor) and Quasar (Gary Lineker’s boot sponsor) as the pair grappled for the Golden Boot in the 1991-92 season- a war Ian eventually won with a typically determined hat-trick against Southampton on the final day of the season.

Nike perfectly captured his cultural capital with an era defining commercial soundtracked by ‘A Tribe Called Quest’s early 90s hip-hop classic ‘Can I Kick It?’ The media were quick to recognise his pop culture attributes and he even presented an edition of Top of the Pops (a very popular music chart show on the BBC) in 1996. It’s no surprise that adidas chose him to front the new kit campaigns last summer either.

Wright’s second goal that afternoon against Southampton, an outstanding solo effort, illustrated the player’s almost supernatural level of determination. As he slaloms through a Southampton rearguard featuring the likes of Francis Benali and Terry Hurlock, the kind of guys that enjoyed inflicting pain, it is clear that he will not be denied. He looks like a soldier dodging landmines and zigzagging away from aerial bombardment.

There were contradictions at the heart of the player that made him catnip for fans. Arsène Wenger summarised it best, “He was such a lively character, but in front of goal he became cold like a killer.” It’s difficult to find a photo of Wrighty not flashing a toothy grin- unless you happen upon a still of him taking a shot at goal. He often looks expressionless in those situations, his eyes still and black.

As a striker, Wright remains supremely underrated. Just watch any random collection of his goals, there is no type he couldn’t score. Right foot, left foot, long range, headed, volleys, chips, unerring close control among a sea of bodies- he really could do it all. It requires hard work to perfect so many different attributes.

In the ‘Ian Wright- Legend DVD’, he talks about working hard on his left foot. “I wanted my left foot to be strong so that when I was in front of goal and the instinct took over, my technique didn’t let me down.” In a nutshell, it’s what made him not just a good striker, but a compelling one. He had a sense of improvisation and playfulness; he would try anything. His instinct was his master, not his servant.

Supporters will always love a prolific goal scorer, but Ian was a street footballer. South American players are often loved for their sense of on-pitch mischief and though no Ronaldinho in the tekkers stakes, Wright operated in an off-the-cuff fashion that us mere mortals, who had never played in academies, could relate to. He tried and executed things you would try [unsuccessfully] at 5-a-side.

He was gloriously unpolished as a player and as a person. Sometimes [often] that coarseness landed him in trouble and his effervescence morphed into frustration. Occasionally he could be childish on the pitch and I recall a recurring discussion towards the end of his time at Arsenal as to whether his fits of temper would blight his legacy.

On the stadio podcast recently, he talked about his ‘sledging’ habit with opposing defenders and goalkeepers. “I would tell them ‘the gaffer identified you, he told me you were gonna give me something today’ even when it wasn’t true.” A little childish maybe, but a lot funny and very relatable.

He slapped the players we wanted to slap, wound up the fans that deserved to be wound up and he often leapt into the crowd and soaked up the adulation when he scored. Being a football fan is to fight a constant battle between being childish and childlike and Wright toed that line. Part of that narrow walk is bound up in fantasy, as fans we constantly imagine ourselves as players and how we would behave and wear our colours.

Just pause and look at the supporters behind the Clock End goal when he breaks the club’s goal scoring record, look at the intensity of the celebrations. Look at what it meant to everyone, ostensibly an individual achievement but one that we all felt like emotional shareholders in. Wright embodied our collective reverie. Which of you hasn’t imagined scoring against Spurs and cupping your ear to their support?

Who hasn’t dreamed of captaining Arsenal, scoring a wonder goal and celebrating by brandishing the armband to the Arsenal crowd as Ian did against Everton in January 1996? It’s why his chant, “Ian Wright, Wright, Wright!” Rang around Highbury so constantly, he was our symbol, our shield, our fiery protector against the forces we loathed.

He knew it too, which made the bond all the tighter. When Bruce Rioch decided to take Ian on in a PR war during the 1995-96 season, there was only one winner. The fans didn’t even need a second look at the evidence, we were on Wrighty’s side instinctively. Wright consciously understood- and still understands- that connection. Even now, through his media work, he maintains that association and his boyish enthusiasm for football that has made him popular beyond N5 during his media career.

His Player’s Tribune piece 18 months ago revealed his humility. Player’s Tribune pieces often risk becoming self-penned hagiographies. Ian used his to consider his flaws, his mistakes and, most tellingly, paid tribute to the people that gave him a leg up when he made those mistakes. He is popular as an analyst and not just because of his enthusiasm.

Ian Wright is about it. A Black British icon.

Always supporting, championing and empowering the generations beneath him.

Climbed high and never lost himself in the process. #NS10v10 ❤️

— Aniefiok 'Neef' Ekpoudom (@AniefiokEkp) May 11, 2020

Strangely given his hyperactivity, he had a calming influence on me as a young fan. I was a very anxious football watcher, but I internalised that anxiety dreadfully. Wright’s presence felt like a release valve for me. You always had the feeling that he would score, that he would make everything ok, too, which certainly helps when your insides are doing somersaults.

It’s probably fair to say that George Graham allowed Wright to become too much of a reference point towards the end of his reign. He slowly dismantled the creative elements of the team and relied on Wright’s instinctive, off the cuff brilliance as a central tactic. For those years in the 1990s, Wright was Arsenal, he was the one that got your colleagues and schoolmates talking, he was the one they couldn’t stand but that they really wanted. He was, and still is, one of us.

Follow me on Twitter @Stillberto– or like my page on Facebook