Passion, desire, determination: it was these factors – normally considered imperceptible in deciding the outcome of a match, (but are quietly crucial) which were evident in Arsenal’s FA Cup final win. Per Mertesacker characterised that best with important tackles and blocks, and generally just lasting the whole match because he hadn’t started a game all season. That example filtered down to the rest of the squad with players winning duels all over the pitch, Danny Welbeck up front hassling and harrying the Chelsea defenders – and even Alexis did some orthodox tracking back.

That’s not to say there was nothing tactically interesting about the game. It was actually a tight and tense affair despite also being and fairly end-to-end because both teams matched each other 3-4-3 vs 3-4-3. At first glance, there wasn’t any obvious weakness in either side’s overall setup and as such, that heightened the little details that made up the tactical battle.

The first advantage came to Arsenal because they scored early and that allowed them to broadly dictate how the game flowed. Their goal, coming within four minutes, was of outstanding quality because it began with a passage of play lasting two whole minutes, and featured 44 passes before the ball went out of play for the eventual corner that led to the goal. I’ve posted that move in it’s entirety below because it highlights the upper hand Arsenal initially had with their interpretation of the system.

The 44-pass passage of play that leads to (the corner for) Arsenal's first goal in the FA Cup final pic.twitter.com/Vw8D43Gwod

— Arsenal Column (@ArsenalColumn) May 29, 2017

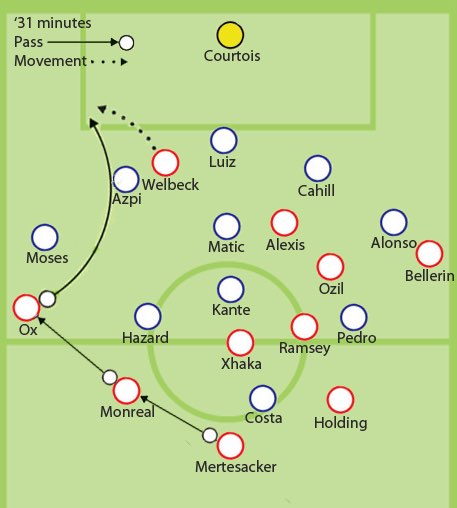

The first thing you notice is that Chelsea don’t press. That was in stark contrast to Arsenal who, at every given opportunity, pushed their three forwards up against Chelsea’s three centre-backs. As a result, that sometimes opened up space in the middle for David Luiz to pass the ball through (though he was often wasteful trying to go direct too quickly) because at the same time, either one of Aaron Ramsey or Granit Xhaka would also push up to try and close down the first pass. But Arsenal coped because they defended tight while the centre-backs were comfortable stepping out and meeting the ball – and were even happy to give away a number of fouls to break down play.

The other difference was that often, Luiz didn’t have a viable midfield creator to pass to. That again, was a result of Arsenal defending tight, using their variant of man-marking to follow Nemanja Matic or N’Golo Kante when the ball was played into midfield. It was easy for Arsenal to do this because for the most part, the two Chelsea central midfielders play in a line.

Arsenal, by contrast, split Xhaka and Ramsey so that it was harder them to be pressed. That led to Arsenal’s early dominance, which you can see at various points in the clip, as Matic has particular trouble getting close to Xhaka. One can imagine that he was tasked by Antonio Conte to close down Xhaka, but each time he vacated the midfield zone to engage him, he left a load of space behind that Ramsey, Ozil and Alexis could run into.

I think you can summarise Arsenal's fluidity by the midfield. Ramsey split from Xhaka whilst Kanté/Matic stayed flat https://t.co/Yxvmvd9tWz

— Arsenal Column (@ArsenalColumn) May 27, 2017

It’s a typical Wenger strategy to split the two central midfielders because, as he says, his philosophy is to play in the opponent’s half of the pitch:

“The teams close us down so much high up because they know we play through the middle. I push my midfielders a bit up at the start to give us more room to build up the game. When you come to the ball we are always under pressure. I am comfortable with that; although sometimes it leaves us open in the middle of the park. We want to play in the other half of the pitch and, therefore, we have to push our opponents back.”

It’s interesting how he’s inserted that strategy into the 3-4-3 because by moving to this formation, it was seen as a grand compromise from the manager, a last-ditch tactical shift borne out of desperation. But he’s interpreted his own spin to the system, and slowly, though perhaps a little late in the season, it’s come into its own. It’s not as rigid as Conte’s 3-4-3; indeed that’s the beauty of playing a back three, as I wrote in one of my last blogs, because of the flexibility it affords managers to use the players ahead.

Now Arsenal can push more players to the attacking half of the pitch without losing defensive solidity. They needed that because in the crucial part of the season, they were often exposed by teams taking advantage of the fact they usually only left two players at the back to defend counter-attacks.

Sam Allardyce explained this thinking when Crystal Palace beat Arsenal 3-0, the defeat that prompted Arsene Wenger’s move to the 3-4-3. “The weaknesses with Arsenal have been defensively,” said Allardyce. “They leave Gabriel and Mustafi really exposed. Monreal and Bellerin play like right and left wingers. The wingers come inside with the centre-forward and they’re just left on their own.”

The increased defensive solidity was evident in the 2-1 win against Chelsea in the way perhaps, the defenders weren’t forced to chase back, but could delay, and then dive in with crucial blocks to stop the shot. The system hasn’t curbed some of the defenders’ impetuousness, but it has cultivated it because they can take risks to win the ball in midfield. That’s one of the reasons why Hazard was so quiet, although he lacked support when he got the ball because Matic and Kante were so deep.

Up front, Danny Welbeck put a great shift in but couldn’t find the finishing touch. Indeed, it’s strange, considering Wenger’s reluctance to sign a deadly striker, that in cup finals, the choice of the number 9 has made a huge difference. In 2014, against Hull City, Wenger brought Yaya Sanogo on to stretch the opposition defence, and that opened up space for Giroud to create the winner.

In the 4-0 win the following year, Aston Villa were terrified of Theo Walcott’s pace thus, they retreated deeper and that opened up room for the likes of Alexis. Welbeck’s inclusion against Chelsea had a similar effect because, frightened of his speed, the back three was unwilling to play a high line. This had a knock-on effect on the rest of the team’s tactics, making it harder to push up and close Arsenal down, meanwhile exacerbating the gap in front each time Matic pushed up.

In the 4-0 win the following year, Aston Villa were terrified of Theo Walcott’s pace thus, they retreated deeper and that opened up room for the likes of Alexis. Welbeck’s inclusion against Chelsea had a similar effect because, frightened of his speed, the back three was unwilling to play a high line. This had a knock-on effect on the rest of the team’s tactics, making it harder to push up and close Arsenal down, meanwhile exacerbating the gap in front each time Matic pushed up.

Indeed, Welbeck particularly likes to play against back threes it seems because the movement away from the wide centre-back means he’s always running on their blind side. Consider his starting position: if he’s initially standing in the middle, in front of Luiz, his next run would see him go behind either the right or left centre-back.

In a back four, the other centre-back will merely pass him on to the other (and a holding midfielder will cover). However, in a back three, there is no holding midfielder and the space is always on the sides especially as the wing-backs push on. The solution is to drop into a back five, which Chelsea normally do, but Welbeck was clever with his movement, constantly spinning off, whilst he was a big threat on the counter.

If the ball was played backwards also, he was there to pounce on David Luiz, meaning there was no easy outball for Matic or Kante. In the end, Welbeck wasn’t rewarded with a goal, but Olivier Giroud, his replacement, provided the winner with the type of run Welbeck was making all game – behind the right centre-back.

Giroud crossed the ball, and Aaron Ramsey stooped in to seal another Arsenal FA Cup win.