As old age begins to settle its claws into your hypothalamus, indeed, into your Frontal, Parietal, Occipital and temporal lobes, distressing things begin to happen. Chiefly, the memory begins to become as flaky and unreliable as Marouane Chamakh. No. Worse. Your memory become like Nicklas Bendnter. And so it was this Friday last when this column returned to Mr. Jobs’ hand held cigarette cases into which everyone on the street seems to stare incessantly.

It was in that column that I traced the new arrivals to Woolwich Arsenal. Graham Shackleton. Present and correct. Terry Ashworth. Luke Perry. Seamus Masterson. But there was an important omission. And one which I will now attempt to remedy.

Arsenal’s defence of recent years has been something of a hotch potch of malcontents, dandiprats and recreant creatures. And so the arrival of Radoslav Holdčević, from FK Metalac Gornji Milanovac, was warmly welcomed.

A little background then.

Radoslav was born in the Serbian town of Gornji Milanovac in 1995 to Andjela, a sheet metal worker and Antonije, a war lord. As a babe-in-arms young Radoslav would amuse family and friends by throwing a rubber ball in the air and booting it out of the door of the family home and into the window of the local priest who lived directly opposite. This has now become something of a trademark move, known as St John the Baptist, as this was the cry from the priest every time young Radoslav launched a long ball through his window and into his potato soup.

Young Radoslav’s first words were “all day”, whenever his mother would try and get past him to the kitchen or the bathroom and he would tackle her with some force, preventing her passage. He could strip down and rebuild an AK47 by the age of four. By six he was martialling the back four of his local school side, OŠ Desanka Maksimović, and they won three regional trophies in a row, also gaining the accolade of ‘Most Glorious and Vicious Proud Fierce Six Year Old Tigers in All of the Kingdom of Serbs’, a trophy held in high regard in Serbia, the award of which was due in no small part to the spiteful and repeated tackles of young Master Radoslav. He introduced some innovative vocal communications to the Serbian game, popularising the following shouts: “Не дозволи да боунце!” (“Don’t let it bounce”), “Гост!” (“Away!”, generally employed when one of his defensive colleagues was in danger of losing possession).

By eight he was playing for Moravica District Under 18s, and also for three works sides; Tipoplastika Wednesday, GRO Graditelj Dons and Rudnik Flotation Superstars. He became so popular that he was immortalised in a Serbian folk song, “Radolsav”:

Он је јак као орао

И агилан као реке

Он је јак као жена

Он је нежан као митраљез

Он је прибор попут Аркана

Он ради као кукавицки Оттоман

Он виче као рибар

Он је проћи као Лиам Бради

Ох! радослав

Ох! радослав

Ох! радослав

Ох! Радослав

Which translates to:

He is strong like eagle

And agile like river

He is tough like woman

He is gentle like machine gun

He tackle like Arkan

He run like cowardly Ottoman

He shout like fishwife

He pass like Liam Brady

Oh! Radoslav

Oh! Radoslav

Oh! Radoslav

Oh! Radoslav

All this of course to the tune of Oj Srbijo, mila mati.

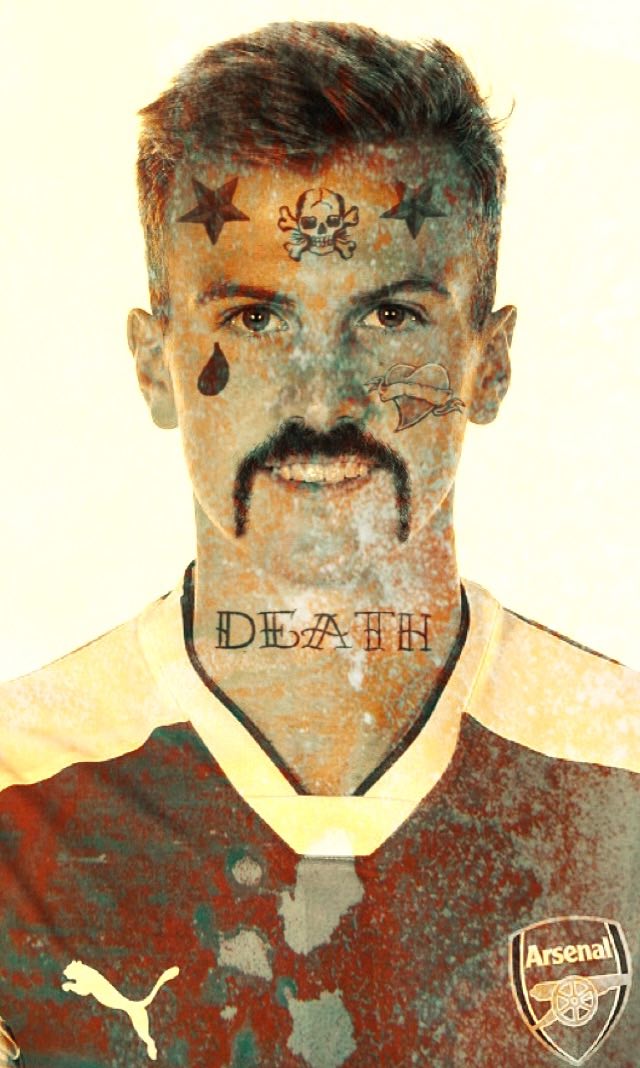

He had a full moustache, just like his mother’s, at the age of 12. He has two stars tattooed on his forehead to symbolise the number of attacking players who managed to get past him. He sports a tear tattoo under his right eye, which he won’t explain, a skull and crossbones in the centre of his forehead (his first tattoo, at the age of nine), and a blank heart tattoo on his left cheek, with the nameplate left blank (“because I have not met my woman yet.” And the word DEATH across his neck. Because, death.

Radoslav has been playing professional football in Serbia form the age of 14, until Dick Law swooped in to Serbia last week and offered an undisclosed fee, thought to be in the region of 200 AK-47s, a dozen rocket launchers and 291,389,411 in unmarked Serbian dinars. It remains to be seen whether he’s worth that little lot but the early signs are most encouraging.

Until next week, “Не дозволи да боунце!”