“We are so unpredictable in what we are doing; even for me at the back sometimes it looks a bit weird! Sometimes we lose balance but sometimes it is really good so we have to keep going and focus on our game.” – Per Mertesacker

I’ve been trying to figure out Arsenal for a while now. Despite my twenty-two-year association with the club (that is, the first game I recall watching them in – Cup Winners Cup in ’95), the last four or five years have left me perplexed. It’s not the lack of titles; I’ve come to terms with the mitigating circumstances following the move to the Emirates and subsequently, the wizardry to keep Arsenal competitive that Arsene Wenger has performed. But rather, it’s the playing style which, despite adding back-to-back FA Cups in the last two seasons, has forced Wenger to be unorthodox – if not innovative –trying to keep Arsenal playing more or less the same way that won trophies in early in his reign (in what was a markedly different era), and to keep challenging with the very best.

I often hark back to the above quote from Per Mertesacker to assure me that even those better placed than I am can find what happens on the pitch confusing. At this point, I realise that the answer that I’m looking for lies in a case study of Arsene Wenger, and because he places such an unerring faith in autonomy and freedom of expression on the pitch, the nuances of the team’s tactics are as much a product of symbiosis as it is moulded by his own hand.

That’s evidenced by the rapid progression of Hector Bellerin from reserve-squad to starter, or Francis Coquelin, who has shaped Arsenal’s tactics the moment he stepped into the first-team last December. It’s a progression which has been a joy to watch not least because it’s usually not this obvious to see a footballer grow. Coquelin gained more confidence game-by-game, becoming “more available” as Wenger says, “and [available] more quickly when our defenders have the ball. He blossoms well.” You can say the same thing about Nacho Monreal, where confidence has shaped him to the point that he seems unflappable at the moment. More recently, it’s the emergence of Alex Iwobi and winter signing, Mohamed Elneny who have affected the system.

The doubts about Arsenal’s system have persisted for some time, but we tend to give Wenger the benefit of doubt in the hope that somehow everything will come together. For many, the patience has finally run out. I find that a lot of people can’t really explain what is wrong with the way the team plays, but know that there is something wrong. Criticisms usually revolves around the argument that the team “plays too slow” or that there is too much focus on “passing sideways” and not enough penetration in the box. Which is all true, though I don’t want to patronize anyone by saying the diagnosis is too basic; the way Wenger wants to play features so many vague lines that the solution (within the framework of his style) is not completely obvious.

Before Arsenal’s 0-0 draw with Sunderland last week, Arsene Wenger gave a stirring and eloquent interview with Geoff Shreeves on Sky Sports outlining the improvements that Arsenal have to make are on the pitch, and the challenge is his to prepare the team better. “The physical levels of teams has gone up and tactical knowledge of defending has gone up,” he says. “Players who do not contribute to team work are kicked out everywhere.

“Then you go two ways: you say ‘look that doesn’t work anymore so we have to change our style, and I wish you good luck when you kick the ball anywhere after people have seen good football for 10-15 years’, or you say ‘we have analysed well where we are not efficient enough and we do better with the style we play’.

“We have to go that way. Our passing has to be quicker, our movement has to be sharper and our efficiency in the final third has to be better. We don’t have anybody with 20 goals in the league, so that is a handicap.”

Wenger had the chance to put his money where his mouth is in the game against Sunderland but the reaction was insipid with Arsenal failing to build on a promising first 30 minutes, eventually labouring to a goalless draw. A similar outcome was seemingly on the cards in Saturday’s encounter against Norwich City until Danny Welbeck came off the bench to score from an excellent Olivier Giroud knock-down. Actually the goal came from a patiently-worked move, beginning at the back with Petr Cech and ending with a delivery and lay-off which were inch-perfect. In between, the ball was moved from right-to-left. and back again, as Arsenal searched for the space to prise open the Norwich defence.

Wenger deserves credit for making a substitution that was initially derided, taking off Iwobi for the striker, which implanted some much-needed dynamism to Arsenal’s play. As soon as Welbeck came on, he cleverly alternated his movements from outside-to-in to provide needed support for Giroud, and he was in the right place at the right time to apply the finishing touch. The relief when he scored was palpable, but Arsenal weren’t able to add to the scoreline because they lacked the necessary conviction, a problem that has been evident in the last few games. Fan discontent has controversially been mooted as a reason for this apprehension in Arsenal’s play and anyone who was at the 2-1 defeat to Swansea in March can’t surely disagree that it has had some effect. Yet, football is inherently an angry place and players must be able to master their emotions – and the emotions in the stands – to their advantage.

The broader issue is that Arsenal’s football is flawed and especially at home, against defensive opponents, that issue is exacerbated. We saw that against Norwich with Arsenal many times, faced with five men strung across the middle, and four behind, finding no way through. As a result, Arsenal were often forced to play the ball from side-to-side before they could find themselves in the position to potentially thread the ball through. Once they got there, however, they were either often crowded out, or play became congested, while the wall-pass up to Giroud was default the fall-back should options dry up.

Passing the ball in this “U-shape” is something that Bayern Munich coach Pep Guardiola particularly derides, and because he was a deep-lying playmaker in his playing days, sets up his team such that everything they do is to avoid being tempted into passing the ball in this movement at all costs. Guardiola takes up this issue in Pep Confidential:

“If I had a line of five rivals in front of me, as usual, they’d want to make sure we could only circulate the ball in a U-like circular movement in front of them – searching from wing to wing for space via the midfield, but never getting any depth or creating any danger. This line of five midfielders would inevitably be tightly pegged to the four defenders behind them – there would be no space between the lines. These two compact lines of opposition obliged me to use space wide in order to avoid danger.

I’d use two wingers – making themselves available on each touchline and capable of going deep when it was the right time. The other attackers needed to move between the two lines. To achieve that I had to lead the line of five astray – move it about, shake it up, introduce disorder, trick it into thinking that I was about to go wide and then – boom! – split them with an inside pass to one of the strikers. And that’s that. They are turned inside out, suddenly having to run towards their own goal. Basically, that’s how I separated my team from others during my career.”

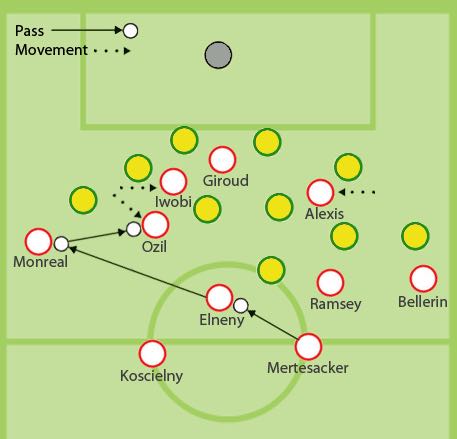

Too often Arsenal are suckered into passing with this U-shape – or rather, Wenger wants Arsenal to because it puts his team in the opponent’s half. He gets apprehensive when the ball is in his own half therefore he tends to ask his deep midfielders to push up the pitch in order to open up space in the centre. In the match against Crystal Palace, which ended 1-1, that tactic proved problematic as it was Francis Coquelin who found himself in advanced positions but lacked the ingenuity to open up the defence.

In the last three games, Wenger realised this problem thus played two passers in centre of midfield, Aaron Ramsey and Mohamed Elneny. Neither are natural defensive players, however, the thinking was that if either one of the two found themselves in the positions that Coquelin did, they’ll have the technical ability and the vision to execute the pass. It worked particularly well in the 2-0 win over West Brom with the pair alternating attacking and defensive responsibilities well, but suffered against Norwich and Sunderland as Arsenal struggled to find fluency.

In the last three games, Wenger realised this problem thus played two passers in centre of midfield, Aaron Ramsey and Mohamed Elneny. Neither are natural defensive players, however, the thinking was that if either one of the two found themselves in the positions that Coquelin did, they’ll have the technical ability and the vision to execute the pass. It worked particularly well in the 2-0 win over West Brom with the pair alternating attacking and defensive responsibilities well, but suffered against Norwich and Sunderland as Arsenal struggled to find fluency.

The problem in these two games was that there was a lack of variety in the movements with play tending to narrow once it reached Alexis and Iwobi, as Arsenal looked for quick one-twos as the default strategy to shift opponents out of space.

For Wenger, style is embedded in attacking strategy so while one-twos come as a result for other “possession-orientated” coaches of well-spaced and ordered attacks, Wenger sees it as a means to open up opponents. He relies on good players to interpret their positions on the pitch and then use sudden changes of pace through quick passing or dribbling to destabilise opponents.

As mentioned before, coaches like Guardiola and Dortmund coach, Thomas Tuchel, or even Luis Enrique or Louis Van Gaal, who are more rigid in their approach, prefer structure over improvisation, establishing superiority with positional play. What they all have in common, however, is the importance of finding the spare man in the build-up and for Arsenal, that player tends to be Ozil. The movements that Arsenal tend to produce in the middle of the pitch, as we’ve talked about, are geared around getting the ball to Ozil in good positions.

At the start of the season, with Alexis and Ramsey making driving runs out wide and Walcott in front pushing defenders back, it opened up space for Ozil to operate more between the lines. However, with Arsenal unsettled by injuries post-Christmas, and teams squeezing that space, Ozil has increasingly been forced to drop deeper and pick up balls from the back of the midfield.

Still, despite being pressed for room, his performance vs Norwich was splayed with some glorious touches and intelligent reverse passes, and his importance to the team was shown in the build up to the goal. To understand what he means to the team, you have to go back forty-seconds before the ball reaches the back of the net with Ramsey slowly advancing with possession, just pointing to Ozil to run into the space between the lines. It might have been a subconscious gesture by Ramsey because actually the space wasn’t there but habitually that’s where he’ll tend to look for him first.

As Ramsey runs with the ball, Ozil just hangs back, towards the left side of the pitch before faking a run into the middle, and then holding his position again at the back of the midfield as he helps advance the play. Welbeck’s presence is important because his introduction brings a freshness to the attack, and once the ball is played to the other side, Ozil zips a pass to Hector Bellerin. The cross, unlike it had been so often earlier in the game, floated in perfectly for Giroud and he expertly laid it off for Welbeck to arrow the ball in.

Tweet: https://twitter.com/ArsenalColumn/status/726816585910988801

The goal brought great relief to the crowd and Wenger, who wouldn’t have looked forward to another press-conference answering questions about another stale performance. As it was, the win managed to stave off a revolt of sorts yet the question marks whether he can galvanise the team remains. If Wenger is not an innovator anymore – and how could he be because it assumes the conditions that brought him earlier success can be replicated – then the relative lack of protest means many are willing to give him one more year to prove that he can adjust, and make his style more compatible to the changing game.