Pressing – the idea that defence begins in attack – is nothing new. Yet, there is a certain mystery about this apparently simple tactic of hassling your opponents to win the ball back. Former Wales midfielder, Robbie Savage, says pressing is most effective when the team hunts together, like wolves in a pack, suggesting there’s an innate instinctiveness to it; about having the will-power and motivation to close down opponents. But even that is overly simplistic: running because you can – and modern players can because they tend to be “taller, faster and stronger, and can press right up to the penalty area” says Arrigo Sacchi – doesn’t make intelligent football.

Roy Hodgson says there tends to be less high-intensity pressing from the front in advance areas these days because of concerns over the “interpretation of the offside law has led to teams to play deeper. Sides are sill compact, but this is mainly in their own half of the pitch.”

The last great pressing team, before the rule-change in 1995 (then what we have now in 2005), Sacchi’s AC Milan, pressed with method, moving up and down the pitch in unison, with defence and attack no more than 25 metres apart. When pressing was pioneered in the 1960’s by Viktor Maslov, it was allowed to flourish because of science. Despite fitness and conditioning being at a peak now (and the prominence of ball-playing centre-backs encouraging it), pressing from the front, high in the opponent’s half, is still thought of as a specialist tactic – as a means to spoil.

However, teams such as Borussia Dortmund and Barcelona have arguably redefined pressing from the front as an essential component of playing. For teams that like keeping the ball, it seems a question of must that you press high up the pitch as a counter-balance for getting organised. Dortmund’s case is more unique as although they retain the ball fantastically well, forcing frequent turnover of possession allows them to control the rhythm of the game.

Arsenal’s style could be said to be in-between both of them: neither as ball-hungry as Barça nor as terrifyingly intense as Dortmund. Instead, their philosophy is to press when the circumstance dictates it, but it starts only once they get into a perfect shape, usually in their own half. Olivier Giroud leads the charge, working tirelessly to put the man in possession under pressure. His role is understated because he’s not really expecting to win the ball back – although it’s a bonus when the goalkeeper dallies as Artur Boruc did in the 2-0 win over Southampton (more on that to come). But he almost acts as a delayer, trying to win time for his team-mates to get into position. Mesut Ozil, schooled in the German way of pressing understands that he must back Giroud up so this usually this means marking the first pass out – or the deepest midfielder. Thus, the instructions for the rest of the team is simple; pick up a man and mark him close.

If Arsenal don’t win the ball back in “three seconds” or so, as Tomas Rosicky says, they drop back into a compact shape – usually in a block as little as 10 metres apart from back to front. For extended periods of the win over Southampton, we saw Arsenal doing just that. Arsene Wenger doesn’t mind so much. His main aim this season is to minimise mistakes, as “he knows last year we lost too many point,” says Santi Cazorla. “The manager is more concienciado, more concentrated, more conscious…he has the same philosophy to keep the ball, play, but in defence, in terms of not committing mistakes, he’s more on top of us.”

If Arsenal are under the cosh, Wenger will obligingly ask his team to drop back and try and weather the storm, then perhaps hit their opponents on the break. Indeed, it speaks of a certain mental toughness they’ve imbued in the last year that they’ve not been overawed when they’ve been asked to drop back. In the first-half of last season, the team’s attacking play suffered when asked to drop back as it asked a lot of the front players to get up the pitch after expending so much energy defending. Thankfully, Arsenal’s form improved after moving higher up the field.

Arsenal’s 2-0 win over Southampton on Saturday was fascinating because it featured two teams who had a very clear idea of their defensive strategies. The Saints had only conceded 6 goals before the encounter and while that meant the match suffered in the way of clear-cut chances, we saw the other side of pressing: how the possession side reacts to the wave of extra pressure.

Arsenal’s answer at times was to move up a gear and pass the ball faster. They were fantastic when they got the ball up to the edge of the box and bumped the ball between each by playing one-twos, but a bit soporific when they had it at the back because that’s when Southampton’s pressure was most intense. The Saints close down more voraciously than the Gunners and when they’re at their best, it can be like a blanket of players attacking the man on the ball at the same time, reducing their options and ultimately draining their self-belief.

In the one real instance when Arsenal overcame Southampton’s pressing, they produced the moment of the match ending with Aaron Ramsey striking the post. The team moved the ball about with patience, switching the play left and right and back and forth three times before Mesut Ozil’s cross eventually found Ramsey. The ball arrived slightly behind the Welshman but it mattered not because he produced an audacious piece of skill, back-flicking the ball – all the power generated through his leap – agonisingly onto the post.

It wasn’t long, however, until Arsenal opened the scoring, the goal coming from a disastrous mistake from the goalkeeper, Boruc, but the unseen part was how Arsenal’s shape denied him of passing the ball out. Granted, Boruc should have just cleared the ball into touch, but it speaks of Arsenal’s commitment that they got organised straight after losing the ball.

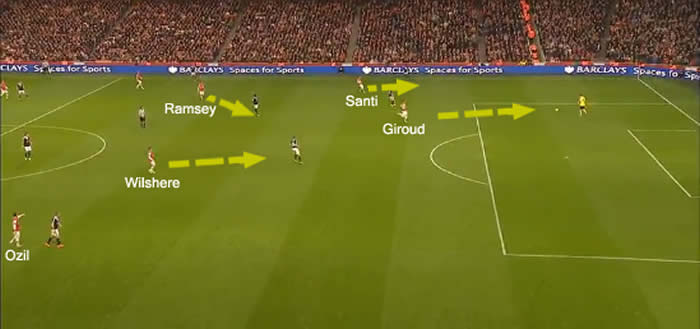

As right-back, Nathaniel Clyne, passed the ball back to the goalkeeper, that was the trigger for the team to move up the pitch. Giroud instantly ran to close down Boruc, taking a little glance back behind him to see if his team-mates were backing him up. They were. Boruc shaped to pass it to his right but couldn’t because Santi Cazorla was there. Then to his left, but Wilshere was alert in case the ball was passed to his side.

By that time, Boruc was discombobulated, his mind unable to process what he should do next. Instead, he tried to take on Giroud not once, but twice, was dispossessed, and could do all but watch with despair as Giroud rolled the ball into an empty net. When Giroud converted the penalty late in the game to wrap up the win, Arsenal had overcome to overcome increased pressure from the away side. But the Frenchman too, had to overcome nerves of his own from the spot, and he made no mistake.

Unlike poor Boruc.