Transitions, the moments when defence turns into attack (or vice-versa), have, for a while now, been considered to be a crucial concept in the modern game. Managers no longer just trade in the major chord inspiration, instead they devote much of their planning on exploiting these momentary weaknesses – when the opponent is disorganised – through the astute manipulation of players and chess-like movements.

Traditionally, this meant winning the ball back in defence or midfield and then moving it quickly to the speed-merchants upfront. Early Wenger sides were a great example of this, taking advantage of the generously high-lines deployed by clubs in the Wild West days of the Premier League, and finding the runs of Wright/Overmars/Anelka/Henry and so on.

However, we saw in the World Cup that transitions these days are just as applicable the other way round, when the team loses the ball and has to drop back into a compact shape quickly. Of course, this is not entirely a new idea as Brazil showed in the 1970 World Cup with Rivelino deployed in a vague left-sided role to balance the vast array of attacking talent in the line-up, and in 1962, with Mario Zagallo shuffling up and down the left-flank to transform the formation to a 4-3-3. Yet, football these days tends to be about universalism where all players must contribute to a dynamic and fluid system. That has given rise to the small, scuttling, scurrying type of player, formerly those that might have played in the number 10 role, but because of their nimble footwork and glide on the ball, considered to be ever-more crucial in turning defence to attack. Because of their altruistic mentality they work the other way too, capable of switching between going forward and staying back seamlessly.

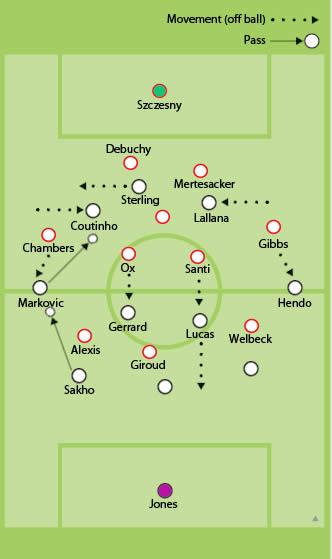

Indeed, looking at the line-ups for Liverpool and Arsenal on Sunday, with both teams broadly looking to control possession, that’s where you would have expected the match to be won and lost. The Gunners started with almost the same team that defeated Newcastle 4-1, with only Calum Chambers coming in for Hector Bellerin, hoping to build on the performance which saw their transition from back to front electrifyingly quick, not just beginning in the midfield with Santi Cazorla and Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain, but with the tigerish Mathieu Debuchy who retained his position at centre-back.

Liverpool’s selection was more left-field, with Brendan Rogers not so much viewing his players as numbers on a pitch, but as versatile, malleable figures, able to adjust their mentality according to where the ball was on the field. Lazar Markovic and Jordan Henderson played as wing-backs while Raheem Sterling, Adam Lallana and Philippe Coutinho completed a diminutive front line.

In the end though, the game followed a more simplistic pattern. Liverpool, with their myriad ball-players, dominated possession while Arsenal were ultimately too top-heavy to impose themselves against high-class opponents, on and off the ball. That in itself is a bit of a regret: we rarely ever see two sides defined by possession go toe-to-toe on equal footing for the whole match: one is usually a cut above the other. The last I remember seeing such a game was in 2010 when Argentina defeated Spain 4-1 in a friendly with near 50-50 possession each.

Other similar encounters, Arsenal’s 2-1 win at the Emirates in 2011 against Barcelona saw Arsenal only accrue 36% of the ball. That, though, after weathering a first-half Barca storm and then having to go Catenaccio in the aggregate defeat away. Pep Guardiola’s Bayern Munich against Luis Enrique’s Barcelona might be the closest we come to seeing possession v possession.

Liverpool thoroughly outplayed Arsenal for much of the match yet on the hour mark; they found themselves behind to the two real chances they conceded. Debuchy cancelled out Coutinho’s opener with a great leap and header, while Giroud finished off a neat counter attack which started with Kieran Gibbs intercepting the ball – just as he did for the fourth goal v Newcastle – and Cazorla cutting the ball back for the Frenchman to strike home. The goal was the only time Arsenal put together a flowing move of note; they were woeful in the build-up phase and Oxlade-Chamberlain, the key player in the transition, looked unfit and often carried the ball for too long.

That in itself summed up Arsenal’s problems; the movement was often static, exacerbated by playing three strikers up front whose naturally tendencies are not to play-make. Wenger tried addressing that somewhat by moving Alexis to the left but too often he opted to dribble instead of playing a quick give-and go with his full-back. Unfortunately this is not atypical of Arsenal, who once again faltered, or flattered to deceive in the big matches. Because so much of Arsenal’s play is predicated on passing the ball well and playing attractive football, thus creating a perception of superiority that is often enough to overwhelm teams lower down. But against the top sides the players (and the manager) seem so anxious to make a statement – a stylistic impression – that play can become very messy very quickly. Paul Hayward of The Telegraph calls this a “conviction deficit”.

To understand that why this happens, first we must understand Wenger. Explaining Arsene Wenger’s philosophy is a trickier task than at first it actually seems. It’s widely accepted that he’s an attacking coach but can that be distinguished from a coach that favours possession first? For example, his Arsenal side do not stretch the pitch as wide as other possession-orientated sides might; instead the Wenger way is to stretch the field vertically in the build up to avoid the press, and then drop a midfielder in to pick up the ball in the extra space. Other teams such as Barcelona – at the far end of the attacking possession extreme – stretch the play horizontally, firstly by splitting the centre-backs and then dropping a midfielder in between.

Instead, the main focus for Wenger is on expressionism and autonomy, cultivated on the training ground by small-sided matches – games of 7v7 or 8v8 – to encourage better combination play.

Instead, the main focus for Wenger is on expressionism and autonomy, cultivated on the training ground by small-sided matches – games of 7v7 or 8v8 – to encourage better combination play.

The importance of possession is preached of course – Arsenal practice a drill called “through-play” whereby a team lines up as it would in a normal match but without opponents, so that the players can memorise where team-mates are intuitively – but keeping the ball must have means: patience is only tolerated to an extent.

This idea of ‘verticality’ works against most sides as they tend to defend deep against Arsenal, and while that throws up problems of its own, Wenger is secretly happy to face those sides as it means they have most of the play. However, it can be a problem when teams play high up, as we saw last season most notably against Liverpool.

In a broad sense, you can argue that Arsenal’s main problem in the 2-2 draw with Liverpool was not with the ball, but their positional discipline off it. However, this game was not an isolated case. They were equally as bad at Anderlecht, Swansea, Dortmund, and West Brom (which being all away matches, highlights there is a psychological factor there too). Putting aside the personnel that were missing, whenever Arsenal got the ball, there was often no opposite and attractive movement.

Instead, players often stood in their positions and found that whenever they got the ball, the best solution was to dribble out with it or pass it long. By contrast, Liverpool’s approach was far more fluid and accurate, with options all over the field. Arsenal’s pressing strategy, muddled by a lack of rigorous detail, was pulled all over the place by the way Liverpool stretched the play horizontally and gave themselves a numerical advantage in all areas of the field.

When The Reds had the ball at the back, Lucas would often drop in, transforming the back three into a four a outnumbering Arsenal’s high-press. The ball would then be transferred to the flanks where the wide centre-back would combine with the wing-back, all the while the front three buzz around the final third, looking to get into pockets behind Arsenal’s central midfield. Liverpool’s chief threat came from when they got the ball to the left, to Markovic or Coutinho, often outnumbering Chambers 2v1 or 3v2, but were let down by poor finishing around the box.

To Arsenal’s credit, they limited Liverpool’s forays into the penalty area by dropping deep, but that was mainly because they were forced to. Flamini was often overwhelmed by the runners around him that the natural thing was to drop on top of the centre-backs and essentially operate as a broken team. Brendan Rogers would have been aware that, despite defeating Newcastle so comprehensively, gaps were there to be exploited, as Stoke did previously, when Arsenal press with the two central midfielders. Unfortunately, the lack of a penalty box specialist denied them of being really penetrative. Instead, pot-shots or cut-backs from the edge of the box were common occurrences.

When Martin Skrtel equalised in the last minute, it was the least that Liverpool deserved though Arsenal had a late chance for a smash-and-grab win with Santi Cazorla. He was Arsenal’s best player on the pitch, the only one who looked like transforming their defence to attack. Unfortunately, his cut-back to find Olivier Giroud was a rare moment of class from Arsenal.