It was Sir Alex Ferguson who once remarked that Zinedine Zidane didn’t “hurt” teams enough. That is, although he could impose his personality on certain games such as the European Cup final in 2002 or in World Cup 1998, considering his stature, he should have done it more often. (Indeed, it’s a view that former France team-mate, Louis Saha, holds as well). As if doing it on the biggest stage wasn’t enough, undoubtedly Zidane’s greatest strength was his ability to dictate the tempo of a football match, killing teams slowly with each touch, pass and swivel, and a swagger which simultaneously propelled his team forward. However, that also led to part of his misunderstanding.

As Rob Smyth writes, “in terms of ball retention he was probably the greatest player of all time, blessed with such grace and supernatural awareness that he could play a game of real-life Pac-Man and never be caught. Yet the suspicion remains that some appreciate Zidane without knowing exactly what they’re appreciating; that they are perpetuating a discourse for fear of being seen as a philistine. Nobody wants to admit that they thought Citizen Kane was crap.”

It’s a similar sort of criticism that has been levelled at Tomas Rosicky. When he signed for Arsenal, he did so on the back of a wonderful strike at the 2006 World Cup, and for fans catching their first glimpse of the playmaker, they thought they’d be getting one who’d mix power with Arsenal’s famed give-and-go style – something that was slowly dissipating following the break-up of the Invincibles side. However, injury problems and age have meant Rosicky had to adapt his game.

Now he’s more of a calming influence, introduced in games for his ability to affect the flow of the contest and to knit Arsenal’s passing moves together. He’s also a fantastic organiser of play, instigating Arsenal’s pressing up the pitch. Rosicky still has that explosive burst of pace, of course, but he tends to use it less as a means to run at defenders and more as a vehicle to switch the emphasis of play, moving into the spaces before anybody else does. That hasn’t prevented people from questioning his value to the team, however, with some arguing that he doesn’t contribute enough in terms of assists and goals. Certainly, his output can improve in terms of raw numbers but that shouldn’t diminish his input to this Arsenal team and against Sunderland on Saturday, though he did just that – score – he showed once against why he’s a valuable member of the squad.

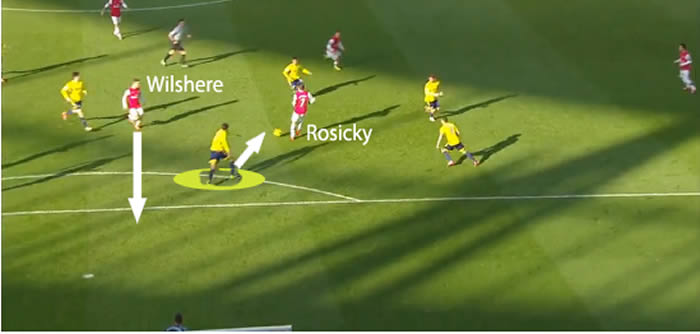

At first glance, Rosicky’s impact for the first goal in the 4-1 win is simple. As Jack Wilshere drives into space, Rosicky moves into the space between the lines and flicks the ball back to the midfielder. But of course, there’s more to it than that. Because the way Arsenal plays, it requires little triggers so that the players know when to move their passing game up a gear. Wilshere does that when he turns inside his marker and lays the ball off but without the flick from Rosicky there wouldn’t be anywhere to run into. However, because Rosicky cleverly positions himself between the lines, it provokes the centre-back, Vergini, to come towards him, momentarily opening up the space for Wilshere to run into. When he gets into the box, he’s squeezed out but Olivier Giroud is on hand to finish.

This is what teams like Bayern Munich and Manchester City do well. They force teams back with their possession play but when they commit runners between the lines, the opposition centre-backs are then provoked to come forward or else be swamped in the box. Arsenal did that all game, bumping passes off Giroud and then making runs beyond him. It didn’t always work and indeed, it poses the question: can this idiosyncratic way of playing, using the striker as a reference, work all the time? Certainly, Wenger feels that the hardest runs to defend are the runs from deep – Arsenal were punished as such in the Champions League when Arjen Robben won the penalty for Bayern Munich – and using Giroud as a pivot can encourage those type of moves.

Arsenal’s third goal was a thing of beauty. Again, Wilshere, Rosicky and Giroud were all involved, as was Santi Cazorla, and the extra runner was enough to confuse the Sunderland defence. As the Arsenal players passed the ball between each other, it reminded me of one of the drills they practice on the training ground called “through-plays”. The drill is basically how the team would line up in a normal match but without opponents so that the players can memorise where team-mates are intuitively and pass the ball between each other. When the ball hit the back of the net, the players could be satisfied with the notion that their hard work produced such a goal. However, it requires something more that is beyond the reach of many other Premier League clubs and an understanding that can seem blind, but when worked on it can be utterly devastating.

I was lucky to be at the game on Saturday and while they were many strong performances – Laurent Koscielny and Bacary Sagna were solid at the back – it was a privilege to see the controlling forces of Mikel Arteta, Wilshere and Rosicky in action first-hand. Arteta in particular was faultless in the first-half, rarely giving the ball away and always choosing the right option, whether that would be playing it simple, or switching the direction of play with a pass wide. He was nearly as good in the second-half when Arsenal had less of the ball, snapping and snarling whenever Sunderland got forward and then ensuring that he stayed with his runners. (Indeed, one example of his diligence was when he quickly sensed that Jack Colback, playing directly opposite Jack Wilshere, was frequently getting beyond him in the first-half, although not getting the ball, so Arteta took the responsibility to stay on him when Arsenal pressed so that he couldn’t get the run on Arsenal’s midfield again).

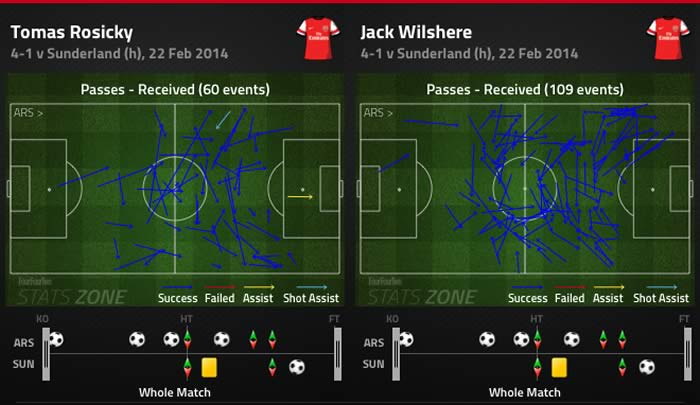

Jack Wilshere gave a more assured performance than he has in recent times, instigating attacks with his drives forward. At first-hand, you’re able to see just how difficult it is to get the ball off him when he runs at you. He has this peculiar dribbling style, almost showing the opponent the ball and poking forward bit by bit with his toe. But his control is so close and his body is always open to protect himself from oncoming defenders. It’s a different way of affecting the tempo of the game than Arteta who tends to do it with his passing (although he attempted over a hundred passes), but once Wilshere runs with the ball, his team-mates know to position themselves in anticipation of receiving a quick give-and-go. Most of the time when Arsenal face teams, they typically defend in a low defensive block and players who can run with and without the ball are key to breaking them down. But of course, with Sunderland opting to drop deep, we didn’t get to see Wilshere’s passing when pressed up the pitch which is his main weakness.

The best performance of the day, though, was from Rosicky who led from the front not only with his passing or his penetrative running, but with his pressing up the pitch. It says a lot about his impact on the side when Wilshere says it was Arsenal’s best pressing display of the season. Simply put Arsenal didn’t give Sunderland an inch in the first-half, closing down the spaces, not necessarily aggressively, but intelligently, moving up the pitch together and marking tightly. Rosicky is almost the free man when Arsenal press because he sets the standard, acting as the reference point.

Strikers always occupy the centre-backs but as there’s only one of them, Rosicky must chose between helping Giroud press one of the other centre-backs or drop off and mark the holding midfielder. For Arsenal’s 2nd goal, the team worked progressively up the pitch, first forcing Sunderland to pass the ball backwards then working the ball wide whereby the touchline effectively acts as an extra defender for Arsenal. Sunderland had no choice but to go back again as Rosicky doubled up with Podolski to close down the right-back, and as the ball went back towards the goalkeeper, Giroud sensed the opportunity to pounce and guide the ball between the goalkeeper’s legs.

Rosicky’s effort lies in the way he makes the whole team play better. His energy and passing were impressive but then there’s the more subtle way he affects his team-mates; Wilshere was able to play better because Rosicky dropped deeper more often in the build up than Mesut Ozil usually does, allowing the Englishman to push forward into space or by opening up space for him to run into by cleverly positioning himself between the lines.

After the game, Wenger rightly gushed about the performance from his talismanic playmaker: “Rosicky is a great accelerator of the game,” said the manager. “He always makes things happen, not with individual dribbling but with individual acceleration and his passing. I think when he arrived here he was less of a tactical player and more the ‘Mozart’ from Prague – he was purely a creative, offensive player. Today he is a real organiser on the pitch, I like to have him in the team because he gives a real structure to our team.”